Your Right to Know Report

Perspectives | 11

The following essays represent the analysis and viewpoints of their authors.

When It Comes to Transparency, the State AG Lags, Fails to Lead

The Washington state Office of the Attorney General (OAG) could be at the forefront of open government. Instead, the agency relies on outdated technology to process records requests, and it adopted a model rule that lets agencies unilaterally close records requests under certain circumstances.

The Washington state Office of the Attorney General is presumably a laboratory and role model for the best practices that all other agencies should follow statewide. But when it comes to public records, the state’s in-house law firm falls short.

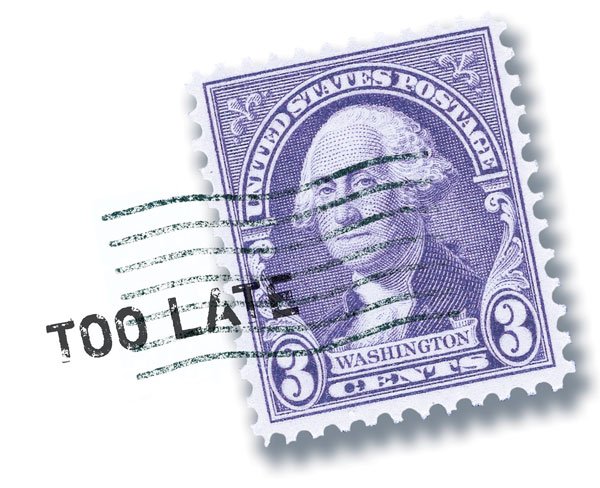

In our digital age the Attorney General’s office continues to rely on payment and delivery procedures for records requests that would sound familiar to Washington residents from the 1800s. We are well into the 21st century, yet requesters must pay the Attorney General’s office for the records either in person or by mail. After getting paid, the agency mails the records to the requester. The process alone takes weeks. In another troubling case of poor leadership, the Attorney General’s office adopted a model rule that closes a records request if the requester fails to pick up or pay for the records within 30 days. On the 30th day, the agency closes the request, and the requester has no recourse other than to resubmit the request and begin the process again.

Both practices are a disservice to requesters who are, after all, members of the public and the media who are trying to figure out whether their government is acting wisely on their behalf.

Regular mail deliveries

Certain agencies turn around requests promptly using internet portals to upload commonly requested records such as law enforcement investigative reports. The advantages of portal access include the ability to obtain the records at the time the agency uploads them. The portal contains the history of all communications and stores the installments in the form produced, which helps track agency action and allows a requester to verify the date, time, and content of disclosure.

Surprisingly, not all agencies use digital technologies intended to streamline disclosures -- even agencies that have the resources and capabilities. For instance, the state Attorney General’s office uses digital technologies for civil litigation where disclosures are voluminous and time sensitive, but it refuses to use the same technologies to facilitate disclosure of public records. (1) The agency has said digital technologies are not reliable or user friendly for unsophisticated requesters. (2) The Attorney General’s office considers sending by regular mail CD and USB storage devices “more efficient for business needs.” Because of this, the Attorney General’s office follows a protocol that consumes at least a month for each installment made available.

The protocol involves the agency sending an e-mail notification that an installment will be made available upon receipt of payment. The agency directs the requester to submit payment by check or money order made payable to the public records officer. A requester must hand deliver or regular mail the exact payment to the Attorney General’s office, commonly in Olympia. The Attorney General’s office then processes the payment. After processing the payment, two-weeks from the date of receipt, the public records officer downloads the installment onto a storage device, CD or USB, depending upon which hardware the requester purchases (CD for $4.09 and USB for $6.38), then sends the CD or USB back to the requester by regular mail. At times, the CD or USB is corrupted, containing no downloadable data. The agency then starts the process over again.

Unfortunately, the Attorney General’s office, by refusing to make digital payment and delivery systems available to requesters, sets substandard protocols for other agencies to follow that discourage prompt responses. Requesters should have the option to pay for and receive records digitally.

Unilateral closures

The Attorney General promulgated model rules urging agencies to close requests if a requester fails to retrieve or pay for records within 30 days. (3) Within the PRA, when requesters fail to claim or review a request, the agency is not obligated to fulfill the balance of the request (4), but there is no 30-day limitation. The Attorney General’s office has propagated the 30 days as presumptively reasonable despite harm to requesters who need access to the information. The agency defiantly adheres to its presumption even when the agency knows for certain a requester has not abandoned their request.

The Attorney General’s office has no procedure to cure a default for a late payment or a missed notification that an installment is ready. A requester’s sole option for obtaining records once an agency closes a request under the Attorney General’s protocol is to restate the same request wherein the agency assigns a new tracking number and starts the whole process over again, which has significantly prolonged responsiveness for requesters. Premature closures harm requesters who seek to enforce their rights under the PRA because once the agency begins responding anew to a request, a requester may be barred from bringing an enforcement action until the agency closes the new request. (5)

The Attorney General’s model rule setting 30 days as a presumptive abandonment of a request should be repealed or amended to enable a requester to cure any default without the penalty of having to make a new request. Agencies should be required to do more than threaten a requester that an agency will close a request at some date in the future after 30 days using boilerplate language in its “installment ready” notices. Agencies should have to provide closure notifications informing requesters of the actual date of closure and that the closure was based upon non-payment. In addition, agencies should be required to inform requesters when the one-year statute of limitations begins to run -- and they should do this when the agency has closed a request or otherwise decided it is taking no further action to respond to the request.

Joan K. Mell is a veteran attorney who works out of her own Tacoma law firm, III Branches Law. She represented WashCOG in its separate open-government lawsuits against the Washington State Redistricting Commission and the state Legislature.

- III Branches, PLLC v. State Office of the Attorney General, Speaking Agent Deposition Transcript, Christina Beusch, Feb. 15, 2023.

- Id.

- WAC 44-14-04005(1).

- RCW 42.56.120(4).

- Hobbs v. State, 183 Wn. App. 925, 335 P.3d 1004 (2014).