Your Right to Know Report

Data Dive

Agency Performance on the Public Records Act

For many years Washington was considered among the most transparent states, but its Public Records Act has been steadily weakened by lawmakers and the courts. The state Legislature keeps exempting more information from public disclosure while finding new ways to withhold its own records. Requesters are waiting longer for agencies to disclose records.

Requesters rarely sue, and what agencies spend on records requests is a tiny piece of their total outlays. Nonetheless, critics often portray the PRA as the source of burdensome expenses and lawsuits.

Statutes and data compiled by state legislative agencies present an evidence-based picture of compliance with the Public Records Act that cuts through some of the rhetoric surrounding Washington state’s embattled transparency law.

- Every year requesters encounter more holes in the PRA, with legislative exemptions up nearly 40% since 2012.

- Requesters are generally waiting longer for records from state and local agencies.

- The number of reported records requests has recovered after falling with the onset of the pandemic in 2020.

- On average, fewer than 0.1% of records requests lead to court claims.

- Records requests account for 0.1% or less of state and local agencies’ annual spending.

- State and local agencies’ timeliness on fulfilling records requests varies widely.

For years, how agencies performed under the PRA was not easily measured by the metrics that our data-driven society has come to expect. That’s no longer the case, thanks to two legislative offices.

The state Office of the Code Reviser for years has compiled the growing list of statutory exemptions to the PRA. The office delivers its annual list of exemption statutes to the state Sunshine Committee.

Since 2017, the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee (JLARC) has compiled performance data from agencies statewide. State and local agencies that spend $100,000 or more fulfilling public records requests must submit data to the committee. With JLARC now in its fifth year of complete annual reports, patterns and trends are beginning to emerge from the accumulated data. The agency released its most recent annual report as our “Your Right to Know” report was in the late stages of production.

Every year, state legislators pass more PRA exemptions

The preamble to the state Public Records Act says, in part, “The people, in delegating authority, do not give their public servants the right to decide what is good for the people to know and what is not good for them to know.”

Yet every year state legislators tell the public what is not good for them to know by passing exemptions to the Public Records Act. It has become routine. Since 2012, state lawmakers have adopted an average of 17 new exemption-related statutes and subsections a year.

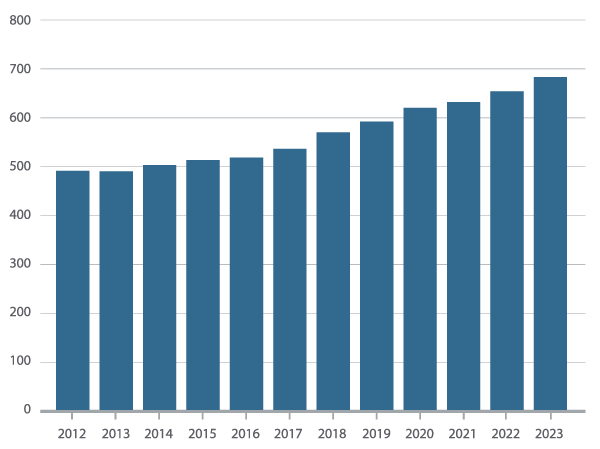

Estimated number of exemptions to Washington state’s Public Records Act, 2012–2023*

*Individual statutes and subsections related to PRA exemptions in the Revised Code of Washington.

Some statutes duplicate exemptions.

Source: Office of the Code Reviser, annual reports to the state Sunshine Committee

The accumulation of PRA exemptions has ballooned in recent years. The Revised Code of Washington had more than 650 individual statutes and subsections pertaining to exemptions in 2023, according to the compilation by the state Office of the Code Reviser. The PRA has been on the books since 1972, but 40% of its exemption-related provisions were added in the last 11 years. At the current rate, individual PRA exemptions could exceed 700 within three years.

As a result, the PRA is increasingly riddled with exemptions that withhold information from the public and make records laws harder for everyone to navigate. The beneficiaries are often interest groups and public officials who want secrecy provisions tailor-made for them. State legislators often oblige.

For example, a PRA provision wisely blocks the disclosure of credit card and social security numbers. But the growing pile of exemptions also includes a statute that withholds a broad swath of information provided by holders of fireworks licenses. More recently, lawmakers have made more information about public employees off limits to records requests.

Agencies are taking longer to fulfill records requests

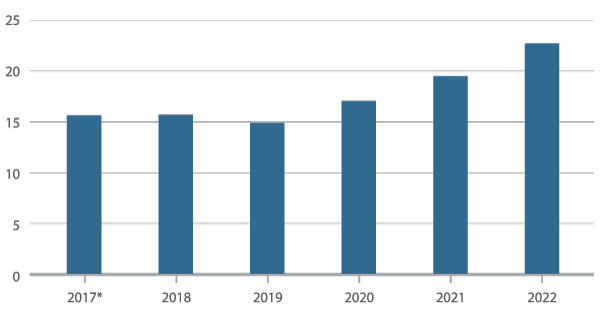

The amount of time agencies take to complete and close records requests has marched steadily upward since 2019, statewide data show. Those who asked for records from reporting agencies in 2019 waited an average of 15 days before “final disposition” of their requests. By 2022 the average wait had increased by more than a week, to nearly 23 days.

Average days to close a records request

2017–2022

Source: Washington state Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee * Partial reporting year, July 23-Dec. 31, 2017

Overall records requests are recovering from a pandemic lull

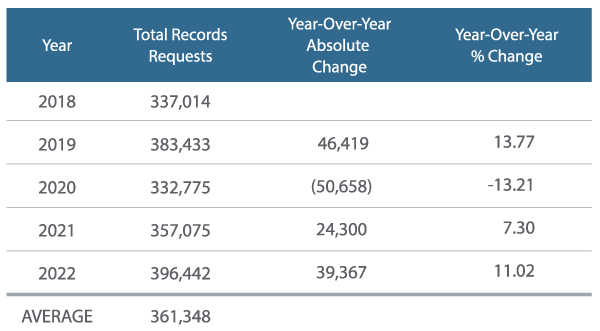

Total reported records requests fell 13% with the onset of the pandemic in 2020 but recovered by 2022. The annual average number of requests filed with reporting agencies between 2018 and 2022 was 361,348.

Number of publice records requests received

from all reporting agencies, 2018–2022

Source: Washington state Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee

On average, fewer than 0.1% of records requests led to court claims

Agencies often complain about the burden of resolving records disputes in court, and their anecdotes frequently leave the impression that records lawsuits are numerous and increasing in number. The data show otherwise.

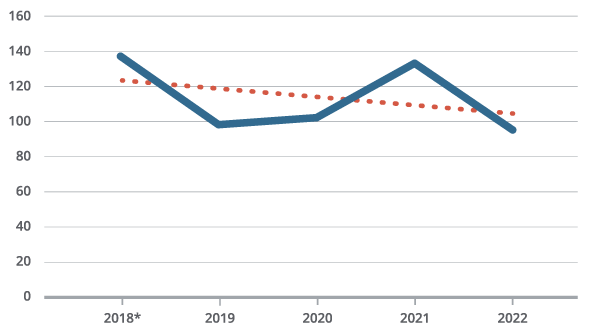

The annual number of claims that requesters have filed in court has been relatively flat since 2018, compiled data from reporting agencies show. The data also show requesters rarely go to court to challenge agency decisions.

Reporting agencies received an average of 361,348 records requests a year between 2018 and 2022. During that time requesters filed an annual average of 113 court claims. On average, an estimated 0.03% of records requests led to a lawsuit.

Nonetheless, state legislators have repeatedly entertained proposals that would make it harder for requesters to challenge agency actions and prevail. Lawmakers often contend such steps are needed to curtail “excessive” public records lawsuits. But in Washington state we enforce the PRA with civil litigation. Proposals that make it harder for requesters to sue and prevail weaken our enforcement of the PRA. Without effective enforcement, our open records laws are more easily evaded. Secrecy spreads.

Number of requester court claims filed against reporting agencies, with trendline, 2018–2022

Source: Washington state Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee

* A Jefferson County report of 870 alleged individual PRA violations filed in 2018 was omitted as an outlier.

That year a plaintiff accused the county sheriff’s office of numerous PRA violations.

(The county settled in 2020.) The remaining cases against all other agencies in 2018 added up to 137.

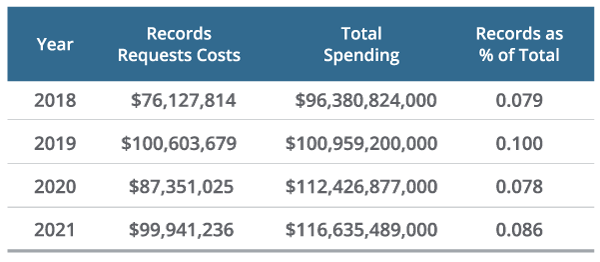

Records requests account for 0.1% or less of state and local agencies’ annual spending

Public Records Act critics often argue that the law is a growing financial burden for state and local governments. But data show spending on records requests accounted for 0.1% or less of total state and local agency outlays between 2018 and 2021. Spending on records is measured in millions of dollars. Total state and local agency spending is measured in billions.

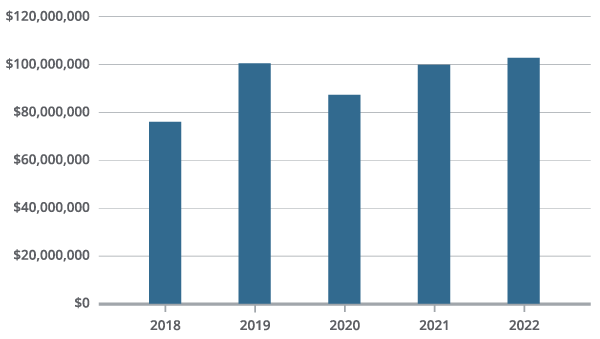

Estimated total cost of fulfilling records requests, by reporting agencies, 2018–2022

Source: Washington state Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee

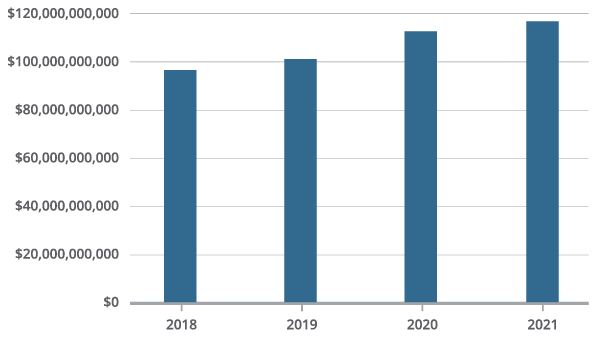

Estimated total state and local goverment expenditures. Washington state 2018–2021

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Annual Surveys of State and Local Government Finances

Estimated state and local government spending on

records requests compared with total direct spending

Washington state, 2018–2022

Sources: Washington state Legislative Audit and Review Committee, U.S. Census Bureau

Some agencies are prompt; others delay – and delay some more

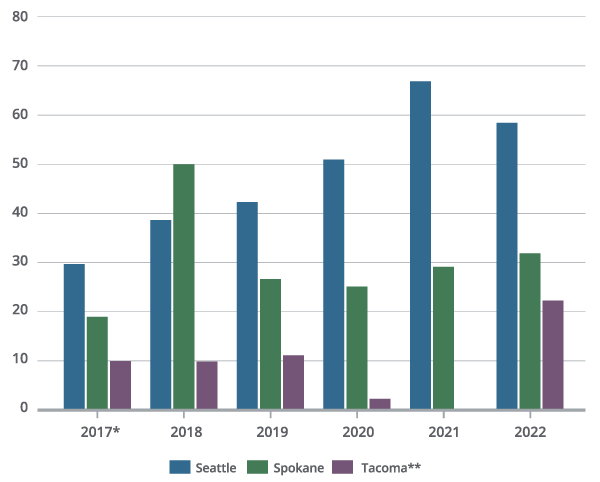

Some agencies make requesters wait longer – at times a lot longer – for records than other agencies, JLARC reports show. The performance of Washington state’s three largest cities is a case in point.

Those who asked the city of Seattle for records in 2022 on average waited more than twice as long for the documents than their counterparts at the city of Tacoma. Seattle has consistently exceeded the statewide average for closing records requests by increments of not days, but weeks. In 2021 requesters on average had to wait an additional 47 days – that’s more than six weeks – to get records from Seattle compared with all reporting agencies statewide.

Average number of days to close records requests

for select Washington cities, 2017–2022

Source: Washington state Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee

* Partial reporting year, July 23–December 31, 2017

** The city of Tacoma did not report for 2021

Source: Washington state Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee * Partial reporting year, July 23-Dec. 31, 2017 ** The city of Tacoma did not report for 2021

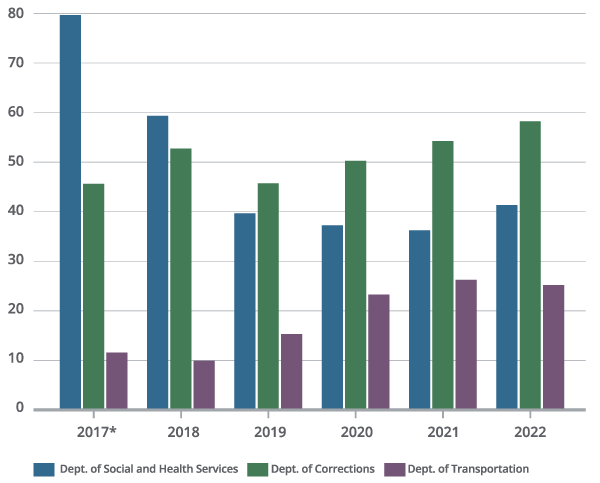

Data reported by the three largest state agencies by headcount provides another example of how PRA performance varies widely.

Between 2017 and 2022, the state Department of Transportation took an average of 18.3 days to close a records request. In sharp contrast, the state Department of Corrections took nearly three times as long – 50.9 days – to close its records requests.

Average number of days to close records requests for

select Washington agencies, 2017–2022

Sources: Washington state Joint Legislative Audit and Review Committee,

state Office of Financial Management

* Partial reporting year, July 23–December 31, 2017

WashCOG Secretary George Erb is a retired news reporter, editor and university journalism instructor. He joined the coalition board in 2002.